Only Connect

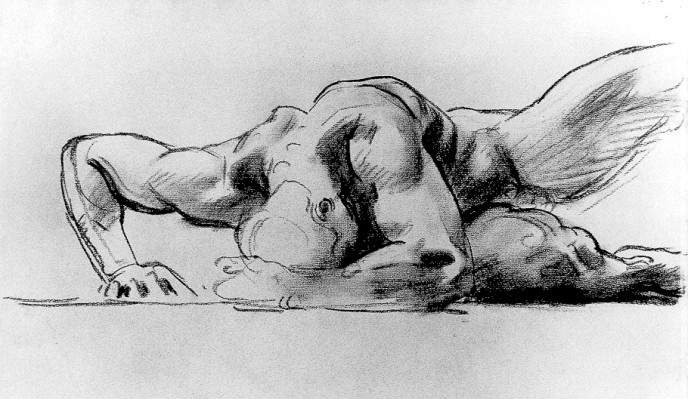

“Orpheus” ( 1908) by Tadeusz Styka (1889-1954); (The Lvov Gallery of Art) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Orpheus’ singing and music transform the world around him and continue to exert their influence even after his death. The combined themes of art’s ability to transform its surroundings and to survive the death of the artist are so ubiquitous in literature that the challenge lies in deciding which few to select as examples.

John Keats, an English poet of the Romantic period, illustrates these themes in two of the most beautiful poems in the English language. In “Ode to a Nightingale,” Keats is temporarily transported from a world plagued with illness and death to an enchanting world in the long ago past, a world populated with faeries and magical beings, a world plush and green and sweet-smelling, a world in which his senses burst into life. The poet’s imaginative journey is triggered by his engagement with the nightingale’s joyous and exuberant song. He is transported to the magical world echoed in the song through the vehicle of poetry, (“the viewless wings of poesy”). It is through art that Keats experiences his vision; and it is through the art of his poem that he takes the reader along with him.

In “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” Keats explores the images carved on an urn and meditates on its ability to freeze the images in time. As a static work of art, the urn transcends the vicissitudes of time. It exists in this world but is not of this world. It can guide us by being “a friend to man,” and allows us to project our ideas, thoughts, and emotions on to its images. In that sense, we “connect” with the urn just as we connect with any work of art and can potentially be transformed in the process. But the connection is not reciprocal. Although we respond to the urn, the urn does not respond to us. It lives in its own self-contained world outside the realm of human experience and is oblivious to our presence.

Although William Shakespeare is known for his plays, he also wrote some beautiful sonnets. For example, in Sonnet XVIII, he explores the idea of art’s ability to freeze time and transcend death. Sonnet XVIII echoes the story of Orpheus in its desire to sustain the life to a loved one. But unlike Orpheus who journeys to the Underworld to revive Eurydice, Shakespeare uses the vehicle of the sonnet to continually keep his beloved alive.

The sonnet begins with a series of comparisons between the beloved and a summer day. The beloved fares better since the summer day is found to have flaws. Shakespeare then declares his verse to be the vehicle by which his beloved retains beauty, youth, and immortality since each reading of his poem brings his beloved back to life. The sonnet becomes a testament to his beloved’s ability to transcend old age and death and to achieve immortality.

As we saw in our discussion, Orpheus loses Eurydice because he violates the conditions given to him by the gods. He looks back when he has been told not to do so. The theme of the disastrous consequences that can ensue if we look back has a parallel in the Biblical story of Lot and his wife in Genesis 19.

In this story, God announces his intention to Lot of destroying the two cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. He orders Lot to take his wife and family and leave the area to escape the destruction. But they are forbidden from looking back at the city while it is being destroyed. Lot’s wife cannot resist the temptation. She looks back and is promptly transformed into a pillar of salt.

Feminists have taken up the story of Orpheus and Eurydice and explored it in new ways. In her poem, “Eurydice,” Carol Ann Duffy provides an interesting twist on the story. She gives voice to Eurydice, allowing her to tell the story of Orpheus from her point of view. Orpheus is portrayed as an arrogant male, obsessed with himself and his needs. Eurydice has no intention of leaving with him and tries to get rid of him. She finally succeeds in getting him to turn around by flattering his ego. She is relieved to be waving goodbye as she recedes into the darkness. The poem is laced with sarcasm and humor.

H.D.’s “Eurydice” similarly accuses Orpheus of arrogance but adds ruthlessness to the bargain. The speaker is bitter and angry at Orpheus for dangling in front of her the possibility of returning to life but then snatching it away from her at the last minute.

Finally, Orpheus’ assumption that he is above the limitations of mortality is reminiscent of Icarus. As we saw in one of my previous blogs, Icarus thought he could fly closer and closer to the sun with no apparent consequence. Just as Icarus is warned, Orpheus is warned, but neither heeds the warning.

Orpheus’ story is also reminiscent of Gilgamesh. The death of a loved one is the catalyst that sets them both off on a quest to cheat death. Gilgamesh wants to obtain immortality for himself after witnessing the horrors of Enkidu's death. Orpheus wants to snatch his beloved Eurydice from the jaws of death and bring her back to life. Both attempts fail.

![Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus (1900) by John William Waterhouse [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ba64bbe4b08d0b7eb54568/1476292186101-8U7NK2PQ6CS41KBWPV1E/Nymphs_finding_the_Head_of_Orpheus.jpg)

![Demeter Mourning Persephoneby Evelyn De Morgan 1906 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ba64bbe4b08d0b7eb54568/1464019116608-VN32SI24A7II6C5WF6GZ/image-asset.png)

!["Landscape with the Fall of Icarus" by Pieter Brueghel (1526/1530-1569) [Public Domain]; via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ba64bbe4b08d0b7eb54568/1452798071320-CS859SDAJDGGE3WL6CHP/image-asset.jpeg)

![Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917); [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ba64bbe4b08d0b7eb54568/1452194379649-B3NMI2M306T6ND5I6S8D/Circe_Offering_the_Cup_to_Odysseus.jpg)